Should I use faced or unfaced insulation?

When planning insulation for any building, choosing between faced and unfaced products can be tricky. Picking the wrong one could mean moisture problems or wasted energy down the road.

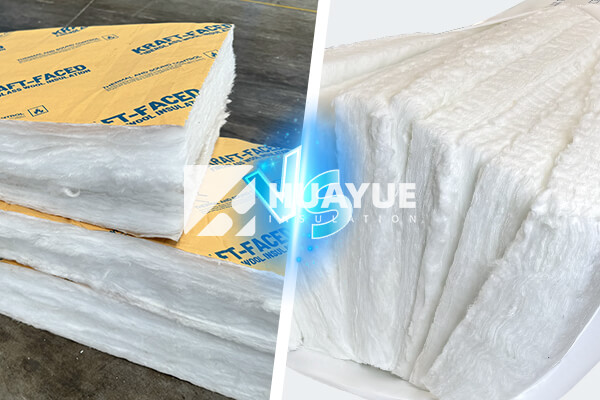

Faced insulation adds a vapor barrier to prevent moisture migration, making it best for exterior walls and attics. Unfaced insulation is fire-rated and fits interior walls, crawlspaces, or anywhere vapor control isn’t needed.

I have helped customers sort out the debate many times. Faced insulation comes with a layer of vapor-retarding paper. Unfaced insulation is simply the fiberglass batt, no extra layers. The right choice depends mostly on location, purpose, and local codes. After years in this field, I always start by asking: what problem are you trying to solve—humidity, heat loss, or fire risk?

What is unfaced insulation—and when should I choose it?

Unfaced insulation works well in places that don’t need vapor protection. It’s Class A fire-rated, so it can remain exposed in some settings, like crawlspaces or interior room dividers.

Unfaced insulation is ideal for interior walls, attics, and crawlspaces. It does not block vapor but allows flexibility and meets fire codes for exposed installations. Hold it in with friction fit between studs or joists.

Unfaced insulation is just the basic fiberglass batt or roll, made to slip between studs, joists, or rafters. Since it doesn’t have a paper vapor retarder, it’s rated as Class A for fire safety. That means you can leave it exposed in approved assemblies—as long as your local rules say it’s okay.

When I work on interior walls or floor cavities, unfaced insulation gives options. It creates a friction fit between surfaces, and sometimes supports or wire are added overhead if it’s left exposed. You can even stack unfaced insulation over another layer (faced or unfaced) to improve thermal performance.

Here’s a quick table that breaks down typical uses for unfaced insulation:

| Setting | Why Choose Unfaced? | Special Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Interior walls | Sound and heat control | No vapor barrier needed |

| Crawlspaces | Fire rating required | Easy to inspect and replace |

| Attics | Add to existing layers | Can meet some fire codes |

| Between floors | Reduces noise and heat loss | Needs support if exposed |

I always remind people that unfaced insulation is for places without vapor migration risks. If you’re working on something exposed or inside a building, it’s often the right call.

What is faced insulation—and why does vapor control matter?

Faced insulation includes a layer of kraft paper, which acts as a built-in vapor retarder. This helps block moisture that travels from warm to cold spaces, protecting the insulation and the building structure.

Faced insulation should be used for attic ceilings or exterior walls where moisture migration is a risk. The paper facing must be installed toward the warmer side, preventing dampness from entering wall cavities.

Faced insulation is designed for places where controlling moisture is critical. That kraft paper layer, often with asphalt backing, provides a barrier. It controls how vapor moves through your structure, helping maintain a dry wall cavity.

When I tackle a new installation in an attic or exterior wall, I almost always start with faced insulation. It comes in batts with tabs for stapling, or without tabs for a tight friction fit. The big rule to remember: the paper always goes on the “warm in winter” side—usually facing the inside living space. Your local building codes can have strict rules about how and where to use it, so always check them before starting.

If you try layering two vapor retarders—say, one faced insulation over another faced batt—moisture can become trapped. That risks mold and eventually damage to both insulation and framing. I never install kraft-faced insulation on top of another facing.

Here’s a quick table showing when to use faced insulation:

| Setting | Why Use Faced? | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Exterior walls | Prevents vapor from migrating | Face toward warm side |

| Attic ceilings | Protects against condensation | Don’t leave paper exposed |

| Basements | Shields against seasonal damp | Combine with proper air sealing |

| First-time installs | Blocks moisture, easy to fit | Follow tab/stapling details |

Vapor control isn’t just about comfort. It’s about the long life of your insulation and your building. I always prefer faced insulation where humidity and temperature differences are most severe.

How do local codes and climate affect the choice between faced and unfaced?

Building location and local climate rules will guide what insulation you can use. Some codes require vapor barriers. Others emphasize fire safety or how insulation is exposed.

Climate and local codes decide if faced or unfaced insulation will meet regulations. In humid areas, faced insulation can protect against moisture damage, while drier climates may allow more freedom with unfaced options.

I’ve worked in places where codes require a vapor barrier, especially in cold climates. In other regions, the fire rating of unfaced insulation is more important. Sometimes building inspectors or architects have the final say. In every job, I check local code requirements first. Sometimes unfaced insulation is allowed for interior work, but faced is needed in external walls. If you’re not sure, contact a licensed installer or inspector before you buy.

Climate also matters. If you’re building in a humid area, faced insulation with a vapor retarder helps stop dampness and mold. In drier climates, unfaced insulation can work just fine, as long as it meets fire codes. The main idea is always keeping the structure safe and maximizing insulation performance.

Here’s a side-by-side comparison of faced and unfaced insulation:

| Feature | Faced Insulation | Unfaced Insulation |

|---|---|---|

| Vapor retarder | Yes (kraft paper) | No |

| Fire rating | Not fire rated | Class A fire-rated |

| Where installed | Exterior walls, attics | Interior walls, crawlspaces |

| Can leave exposed | No | Sometimes, if code allows |

| Can be added to layers | No, avoid double vapor barriers | Yes, over other insulation |

| Installed orientation | Facing toward warm side | Friction fit, any direction |

Always check your local code before choosing. It’s not just about insulation—it’s about the safety, durability, and compliance of your building.

Conclusion

Faced insulation is best for vapor control in exterior walls and attics, while unfaced fits interior walls and places needing exposed, fire-rated solutions. Always follow your local codes for safe installation.

You may also be interested in:

Ready to Get Started?

Get in touch with our experts for personalized solutions tailored to your needs.

Get Free QuoteLatest Articles

Let's Work Together

Ready to take your business to the next level? Get in touch with our team of experts and let's discuss how we can help you achieve your goals.

Get Free Solutions